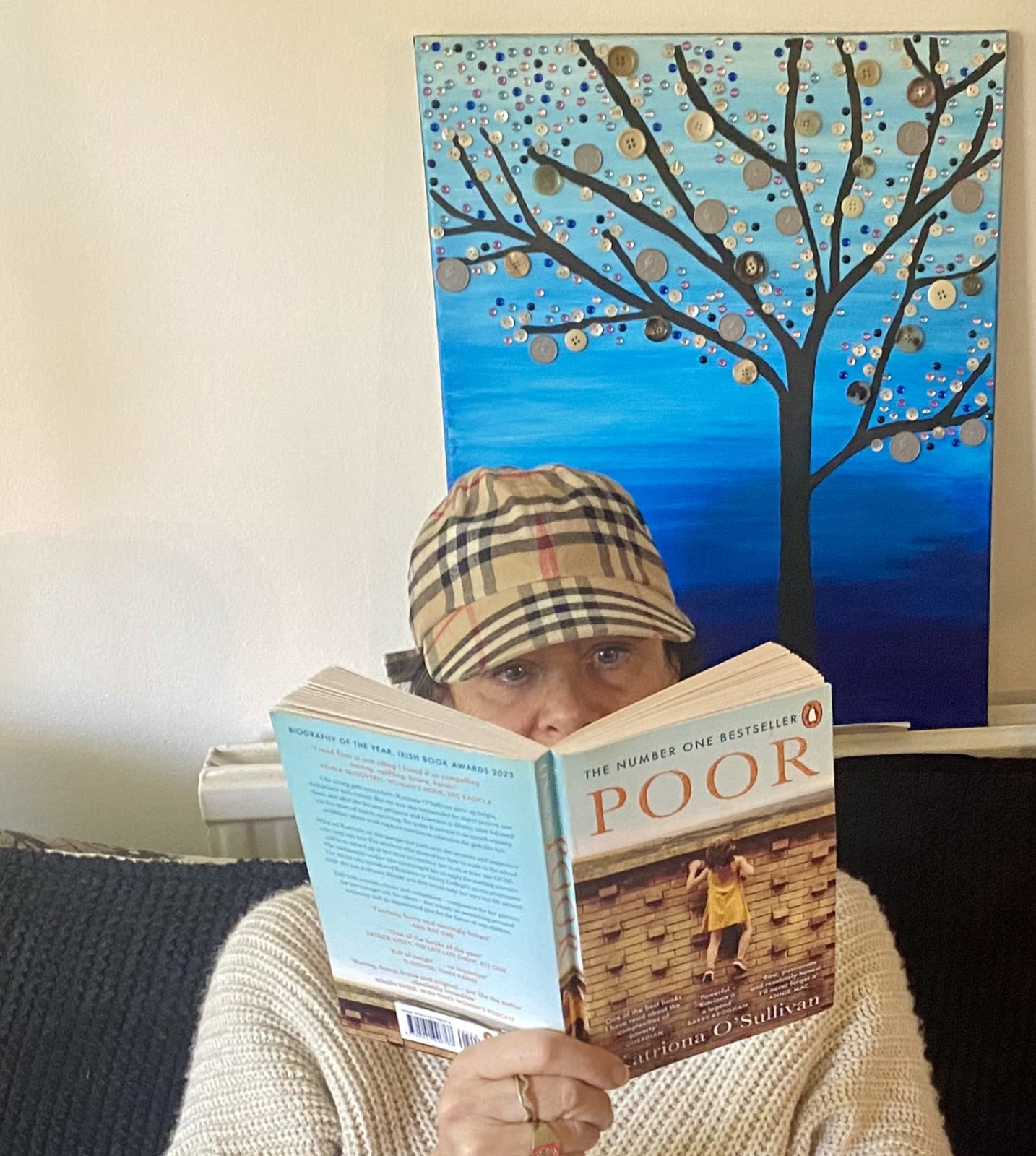

As much as we’re fascinated to know how the wealthiest live, we also ought to know how the poorest exist. Cue Dr Katriona O’Sullivan who has bravely shared her story in a novel that is being enthusiastically embraced. First published in 2023, Poor was immediately selected as Book of the Year by eight UK and Irish media platforms, and this year it’s been a bestseller for Penguin Publishing. Dr O’Sullivan, now a teaching Doctor of Psychology who lives in Dublin with her husband and three children, has become a reference point for understanding the consequences of poverty and the trauma of drug addiction. Here’s a woman who didn’t regularly brush her teeth until she was in her twenties and who as a child thought of herself and her siblings as “pups of scum.”

The novel begins with the neglected six-year-old Katriona having to witness her father overdosing, again. “Pissy pants” Katriona doesn’t know how to wash and wets her bed every night in a home with no towels, toilet paper or soap. For her a sandwich is bread and sugar, freedom is a patch of grass at the back of their first house in Coventry. Drugs and alcohol keep her parents going. Despite constantly seeing her parents passed out with a needle in their arm or leg, Katriona the innocent yet not ignorant child, is forced to have a relationship with drugs. She sees how heroin makes her mother calmer than booze and recalls how frightening it was “to see someone you love sick from drug withdrawals.” Aged seven, just before a six-month stint in a good care home which should never have “sent her home to starve and stink,” Katriona is raped by one of the ‘uncles’ who smoke, drink and deal all day in the family home. Then her life becomes a ‘before and after’ and the new guarded Katriona feels like “a butterfly on a board.”

O’Sullivan writes without self-pity or anger. Rather this author presents fact after fact and gives the reader space to emotionally respond. Towards the end of the novel when she is reflecting on her childhood, she concludes that poverty is the feeling of having no worth and it’s her greatest regret. Along with the lack of material possessions she writes, “It was poverty of mind, poverty of stimulation, poverty of safety and poverty of relationships.”

Despite extreme deprivation, O’Sullivan’s optimism sings loudly; and as an adult she believes that a childhood spent having to read other people’s unpredictable moods and needing to outsmart them has contributed to her capability in her psychology studies. Her better memories such as of the people who gave her vital praise and the support to show her how she could control her fate, enable the reader to be held in hope. There are the two reception year teachers who daily gave the little girl clean underwear and later, a youth worker whom Katriona could talk to – “He was the king of the safe space. A builder of confidence.”

So often it feels like Katriona is unnecessarily punished by narrow-minded and unfounded judgements and especially in her relationship with men. She writes that from twelve years onwards she felt “fully responsible” for how men spoke to her and the way they groped her. Like her mother and her nan, she believed that her value depended on how men appraised her. In her need for approval and the search for Mr Right, teenage Katriona is used, abused and blamed for provoking those who hurt her. As for authority, such as police and social workers, Katriona is taught to be “instantly mistrustful” to survive and the way that she is treated by some of them makes her feel less like a “victim” and more like “vermin.”

Although as a young adult Katriona struggles to allow herself to dream of living a life untypical for the “underclass,” she receives holistic support from the Dublin Trinity Access Program and the Irish government which, in her opinion, had enough money in the late 90s to give people in crisis the services they needed. Throughout Poor we see that courses, centres and safe spaces are key to Katriona’s self-improvement especially when as a fifteen-year-old school dropout forced out of home and squatting with her baby, she starts spiralling.

Too often Katriona appears to be caught between equally difficult choices. She remembers in her later teens taking out her pain on “the people who had it all” by joyriding and robbing and yet when she tries to “cut the rope” that is dragging her back down into the trench of poverty, she feels guilty for abandoning the role as her parents’ “babysitter and referee” or she is chastised by siblings and friends for not sticking with her own. In the wider society she struggles against her comfort zone which she describes as “fear and failure.” For instance, unlike most first-time mothers, she can’t admit she needs to be shown how to feed her baby because the weight of her label – “gymslip mum” – is too heavy.

Thankfully this is a story with a happy ending. After being pushed and pulled by people and circumstance, after all those formative years of believing she’s “trash,” what a triumph to read of our heroine earning a doctorate in psychology and at the award ceremony she’s shaking hands with Mary Robinson the first female President of Ireland. As cathartic as the writing of Poor must have been for Katriona O’Sullivan, this novel is now a gift to enrich many lives – a voice for those in need, a window for those who can’t know the struggles of the poor and a compelling read for lovers of good literature.